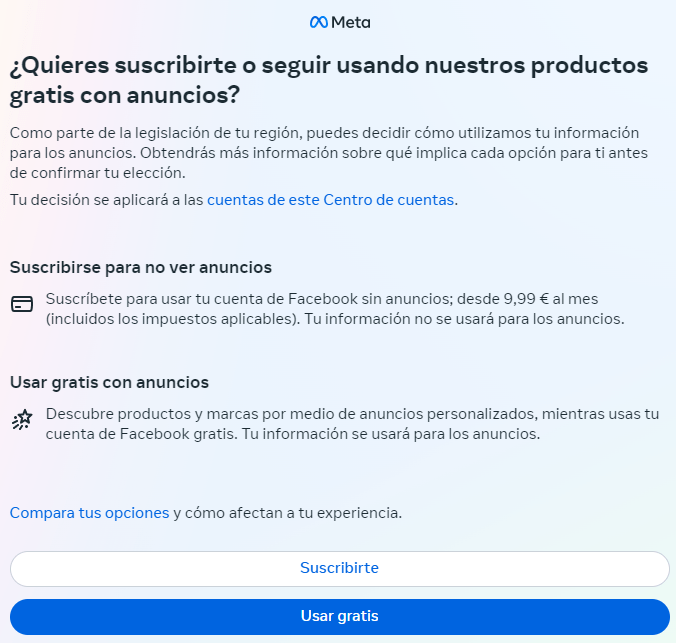

As a response to EU regulations (GDPR and DMA) Facebook proposed a paid subscription to Facebook and Instagram (by paying 9,99 €/month + 6€/month for each extra account of yours in Meta Account Center). These subscribers will enjoy ad-free services and Meta will not process their information for personalised advertising.

From a legal perspective, there seems to be a huge controversy on the topic with different views from different DPAs across Europe. Recently, the EDPB has adopted an opinion on the topic. The bottom line is that «offering only a paid alternative to services which involve the processing of personal data for behavioural advertising purposes should not be the default way forward for controllers» and «does not comply the requirements for valid consent». They ask for a free alternative without behavioural advertising.

Different kinds of paywalls have long been used by the media industry to find additional sources of revenue online, challenging traditional beliefs that access to online news is free, and achieving disparate subscriber rates across countries. In most cases, users pay for content on online news sites, whereas the so-called cookie paywalls allow users to choose between consenting to cookie tracking and paying a subscription to use the website tracking-free. These are definitely closer to Meta’s case, except for the fact that Meta has been designated as a gatekeeper according to the DMA.

From an economic perspective, Facebook and other sites behind cookie paywalls have basically set a price for their users’ privacy. Pending some clarifications regarding what happens with previous information already stored and with the processing of personal data for other purposes, In Europe, Meta is asking a user 15.99 €/month for getting rid of ads and enjoying privacy in their Facebook and Instagram accounts. Moreover, recent works have located more than 300 sites with cookie paywalls, most of them in Europe and with average consent being worth 75 €/year and 40 €/year for a website in the two versions of this study. Furthermore, a company is bundling ad-free access to the content of more than 450 websites for 3.99 €/month, an interesting tweak to the cookie paywall business model. Check how many sites you visit every month and sum to find out how much the industry is pricing your privacy. Yet, only time will tell how many consumers are up to paying Meta and companies sunning cookie paywalls for keeping their data private.

This reference add up to the results of many existing methodologies to estimate the value of data. An interesting paper on the topic echoed the results of a study concluding that an average US Facebook user should pay US$48 per month in compensation to forgo their data. Interestingly, this paper also presents several practical examples of models estimating the value of data using very different approaches… and obtaining very different results.

This topic is, at least, controversial. Recently, I had the opportunity to participate in a workshop on personal data usage at the ITU. To support a dismissive opinion on the value of personal data, one of the panellists referred to an interesting (though opaque) document published by invisibly.com a Personal Information Management System (aka PIMS). This webpage in turn refers to a study by YouGov and MacKeeper back in 2020 that highlighted the differences in the value of personal data from different demographic groups, reporting a range from US$0.01 – 0.36 per person. I resorted to Google’s cache to find out more about the study since it was removed from MacKeeper’s website, and it seems to be based on national surveys and measures willingness to pay for massive personal data to build marketing audiences. Therefore, restricting the value of personal data to this particular case and survey is questionable . Interestingly and more unique, Invisibly provides more references of the prices paid for different types of personal data in the dark web. The most valuable asset is health records (sold for more than 250 US$), and credit card transaction details (3 US$). Unfortunately, they provide no references or further information about where and how they obtained this information.

What I agree with this panellist is that data markets are not work properly nowadays. This is because of the elusive nature of data as an economic good, and also because of the enormous challenges that must be addressed to bootstrap data markets.

In the meantime, the value of data lies in its versatility and reusability, i.e., in what data-driven companies can make (investing and after great effort) out of it. Take online advertising, for example. According to IAB, online advertising revenues reached US$225 bn in 2024, which divided by 333MM Americans results in 675 € yearly advertising revenue per potential user. This figure is much lower in Spain, 5.000 MM€ revenues in 2023, which divided by 48 MM people results in unit revenues around 105 € per person. When interpreting these figures, take into account that not all this money comes from targeted programmatic advertising.

And online advertising is just one way to use personal data. There are other promising use cases, such as credit scoring, using medical records to improve and optimise healthcare, and crime analysis, to name a few. In a recent study, we surveyed data products being offered in data marketplaces and we found out that the most valuable personal data are credit card transactions and location data from individuals. These are valuable inputs for use cases related to marketing or commercial planning.

Some studies have attempted to give a more macroeconomic figure to the potential value of data in the economy. In its daring book Radical Markets, Eric A. Posner and E. Glenn Weyl state and estimate that a family of four in the US would receive 20k USD per year if they were paid for the data they give out for free to online platforms.

In conclusion, it seems pretty obvious to me that personal data is very valuable. It is so valuable that a whole ecosystem has flourished just around online advertising, and that, as some authors claim, the whole digital industry is supported by the behavioural surplus of our personal data.

So, the real question is how this value should be distributed across the chain, whether data is like sand, and the value is in the complex processes of transforming data into valuable services and insights, or data is more like labour, which means acknowledging users’ role in creating data, allowing users to opt out, and even granting an income for the use of their data. In terms of public policy, this leads to a sort of tradeoff. Whereas public policies that align with the former view aim at incentivising the digital innovation ecosystem around personal data to achieve a greater good, those aligned with the latter are more concerned with the end user’s rights and often blamed for undermining digital innovation. Even when this can be the case in the short term, betting for user-centric approach may also foster innovation and require huge investment to build fair data-as-labour markets in the long term.

There you are! An interesting debate to follow in the years to come. Thanks for reading!

Deja un comentario